Written by Bhagath Subramanian.

Art exhibitions tend towards abstracting representations of reality, or certain aspects of reality such as various emotions, time periods, or experiences, through the narrative laid forth by the inter-spatial relations between artworks. Place one piece next to another and the space between the two comes alive with their mutual interaction, each one’s aura and meaning to the viewer affecting each other. It is then clear that the particular configuration of artworks in an exhibition space can be used to convey various narratives, using artists’ pieces as nodes in a wider experiential fabric, providing context to each other, thereby giving life to an abstracted reality far greater than the sum of its parts. One example would be the Contextual Cosmologies exhibition held in late 2023 to early 2024 at Kerala’s Trivandrum College of Fine Arts, where artworks by Kerala based artists were placed throughout the gallery in a manner so as to provide viewers with an experience of walking through a dynamic exploration of Kerala’s history, its politics, its people, and their relationship to the land and each other.

This understanding allows the viewer to examine intended or unintended functions of an artwork, group of works, and the space in which they are exhibited, especially when applied to unconventional subjects. One such subject that I encountered recently was an exhibition in New Delhi at the Kamaladevi Complex, held by the Japan Foundation. The show was titled I Love Sushi and was compiled under the supervision of Hibino Terutoshi, a research authority on sushi. The show was set up with the intention of educating people about sushi, as a form of cultural exchange sponsored by the Japanese Embassy. The show is concerned with the preservation of and the education about the culture behind Japanese cuisine, which the show’s booklet states as being a UNESCO listed Intangible Cultural Heritage.

What interested me most about the show was that instead of opting strictly for a style of exhibition more reminiscent of museum display, the show was interested in bare bones simulation of the experience of visiting an authentic sushi restaurant in Japan. The gallery space’s entrance is furnished with a traditional style sushi bar curtain. The space itself is filled with dozens of accurate replicas of a wide range of sushi varieties, complete with a revolving carousel of sushi dishes that go on in a loop, and a table where the viewer can sit and watch as a life size video projection of a sushi chef prepares them a meal, complete with a second screen on the table so that the viewer can view a top down view of the sushi chef’s hands. At the back, the viewer can find prints of traditional sushi related woodprints, and museum style sculptures of the fishes and cephalopods that are traditionally used in sushi.

The I Love Sushi exhibition uses simulation to abstract aspects of sushi culture. Unlike most attempts at simulation, such as videogames, flight training modules, particle physics systems, VR pornography, military training, and molecular structure modelling, there is not much of an attempt at a high fidelity experience. The goal of the exhibition is not to make one feel as though they are actually in a sushi restaurant going through the experience of ordering a meal, watching it be prepared, and consuming it. The reaches at simulation are light, brief touches, such as the virtual chef, the looping carousel, and the vast display of replica sushi. The high fidelity aspects of the show can be found in the details. The replica sushi is almost indistinguishable from the real thing, the chef is filmed in high resolution and with a staggering attention to the motion of his hands, and the replica sea creatures look beyond photorealistic.

The exhibition, this art show functioning as an ark of culture, is a unique sort of simulation in that its works do not strive to be the star of the show. The show uses the scenographic language of an art exhibition to convey intangible aspects of Japanese culture, but never truly fully simulates it for us. There is no release for the viewer. The usual sort of pleasurable release that comes with the contemplation of an artwork, jouissance, is also absent, primarily due to one interesting aspect of the show, that being the fact that the object of contemplation in I Love Sushi is never the works on display. When the viewer is studying the replica sushi or watching the virtual chef, one is not primarily concerned with the artistry that went into the creation of these artefacts. The craft and its admiration is not prime. Despite the works taking centre stage in the show, it is something else that is the object of contemplation, which is the intangible and tangible aspects of sushi culture.

Had the contexts placed on the show been any different, the admiration of craft would be prime here. However, the contexts for the show created by Japan Foundation is the celebration of the culture of sushi. The paratextual aspects of the show and the contexts it creates transforms the spatial language of the pieces in this show, turning them into nodes in a wider fabric whose primary concern is the larger cultural narrative of sushi. They exist purely as signifiers of things that do not exist in that room, as opposed to most artwork that are primarily concerned with the display and exaltation of their own aura. I Love Sushi is the most honest sort of simulation, because it never invites you to stay within its bounds. It uses context and scenographic grammar in a boldly simple way to communicate an abstracted aspect of the reality of Japanese culture. It never claims to be a stand-in for reality. It is a show of replicas and simulations that is in tune with the material world, with a very simple message, one that invites the viewer to try out something new, something real, something that you might find delicious and spiritually affirming.

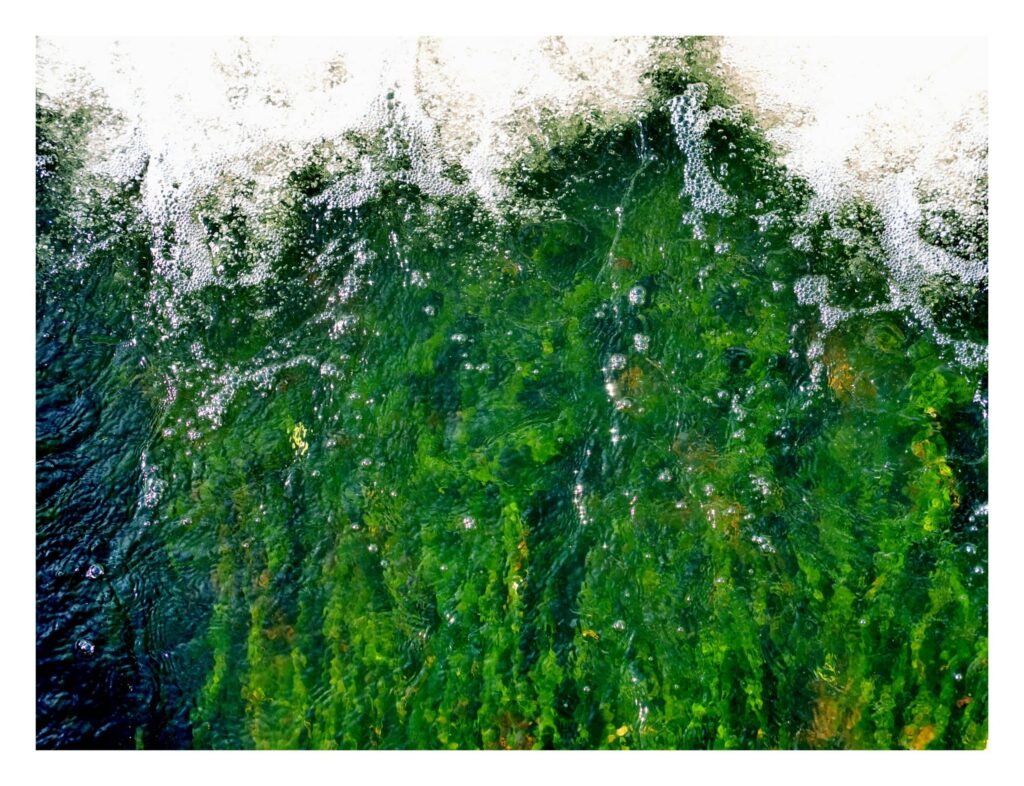

Cover photograph by Bhagath Subramanian.

© Bhagath Subramanian. All rights reserved.